Scott Joplin: Feminist Icon

By: Lila Gilliam, Olivia Duever, Elaine Ransom, Iyanna Herring, Mara Suggs

Before We get in...

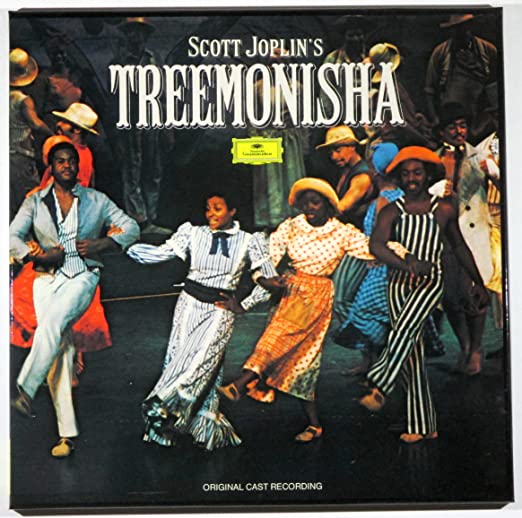

Since we are studying music, unfortunately, our role in creating a post this week is not to analyze exactly how Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha pushed the boundaries of the society at the time it was written in 1911. However, we simply cannot make this post without emphasizing how exactly this opera was revolutionary and that Scott Joplin was a “woke king.”

Reasons why Treemonisha was ahead of its time, and even remains ahead of "THIS" time

At the beginning of this opera, it is very clear that this opera is not like other operas before it. For one, the style is ragtime, not the traditional sort of opera that we associate with Western Europe. Even today, modern operas still stick to the traditional style of singing and orchestral music, while the costumes are more updated to today’s standards.

The title character, Treemonisha, is an educated Black woman and a leader in her community. In 1911, minstrel shows were still popular. To make an opera about a Black woman, not mock her, and strongly hold to that she was educated? And have a Black man write it? In a time where women couldn’t vote and the equality of women was not anywhere near where it is today? Ahead of its time. Even today, popular movies and shows still write both female and Black characters to fit harmful stereotypes.

Joplin was able to paint this dynamic portrait of black womanhood with Treemonisha. He is able to tackle and address various topics regarding race and gender through her character. It is through the music selection that we can see these ideals.

Also, there is a feminist twist to how Scott Joplin named the main character. Treemonisha is named after her adoptive mother, not after her adoptive father, which was common in this time.

Monisha

In their article titled “Uplift, Gender, and Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha,” Rachel Lumsden analyzes several songs from the opera and how they fit the intentions, attitudes, and personalities of the characters. Between the other music majors/minors in this class, I was designated to analyze Lumsden’s analysis of Monisha, Treemonisha’s adoptive mother.

There is not much that Lumsden analyzed about Monisha’s lyrics and notes. However, Monisha is mentioned in Lumsden’s analysis of the song “The Bag of Luck.”

Lumsden writes

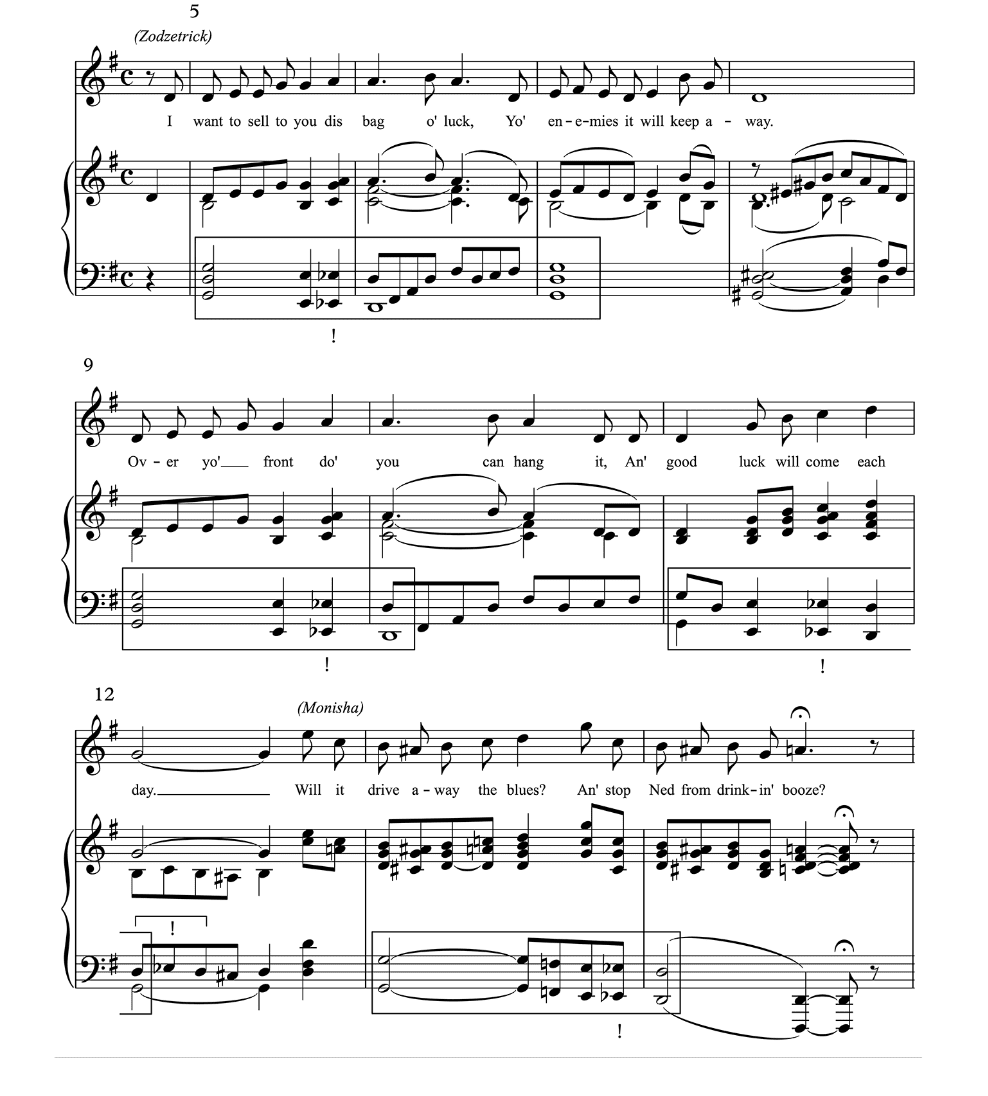

“Flat scale-degree six (e-flat) appears prominently and repeatedly from the very beginning of the quintet, where it is the only chromatically altered pitch featured during Zodzetrick’s opening music in measures 5–7. Yet this bass line—g, e, e-flat, d, g—is used as a kind of motive throughout the open-ing of the quintet, as it returns not only in Zodzetrick’s first measures, but throughout his entire first period, appearing also in measures 9–11, again in diminution in measures 11–12, and even in Monisha’s following phrase, measures 13–14 (see Ex. 4). In each of these moments, ♭6ˆ does precisely what we’d expect it to—it resolves down to 5ˆ, strengthening the pull to the dominant.”

This is exactly how I expect Monisha’s character to behave. Parents are known to resolve conflicts and the fact that Monisha’s phrase resolves is a clever addition by Joplin. I’ll be honest, I’m truly a chemistry major and I haven’t yet taken music theory, but I do know that when a chord resolves, a different, harmonic sound results, which makes sense, since there is a conflict that directly involves the villain, Zodzetrick, and her daughter, Treemonisha.

Treemonisha

As previously mentioned, Treemonisha is the heroine of the opera. She uses her mind, power, and strength to restore and lead her community. In Rachel Lumsden’s article, she mentions that the musicality of Treemonisha’s voice part is reflective of her journey and role in the opera. She makes this commentary in contrast with the opera’s villain, Zodzetrick. While Zodzetrick’s music is full of diminished chords, minor keys, and menacing motives, Treemonisha’s voice balances with his to destabilize and even overpower Zodzetrick’s in the end.

She sings many notes as high as A5 and B5, Lumsden notes, that uplift “her community as it soars well above the voices of her neighbors…” (56) The author also notes that “Treemonisha’s uprightness, purity, and erudition are musically emphasized by her consonant and virtuosic… melodic lines, and her avoidance of the shiftiness and ambiguity of the dissonant diminished-seventh sonority associated with Zodzetrick.”(57) I agree with the author as I believe that composers typically write to further drive the feeling and emotion they wish to convey. The major chords that Treemonisha sings sound much more pure and joyful than the diminished and dissonant ones that Zodzetrick does. The specific chords that Joplin highlights in Treenonisha’s songs are used to foreshadow to the audience Treemonisha inevitable victory despite the vast contrasts of power between her and Kodzetrick within the beginning of the opera.

I believe that Joplin does this intentionally to add drama and suspense to the plot of the opera, but also to differentiate the difference in the character’s character. The efforts Joplin took to produce the characters’ sonic contrast while still making the opera musically coherent were not lost in vain. I thoroughly enjoyed the twists and turns of the opera’s musicality. Especially in the climax of the opera “We Will Trust You As Our Leader”, Lumsden writes that in this section, Treemonisha really walks into the power that she has always possessed within. “Just as Treemonisha vanquishes the evil conjurors through her principled leadership and rises to lead her community, so too is the ♭6 motive ultimately “uplifted” musically…”(65). Treemonisha’s voice and music entirely reflects her character as a leader and woman of grace and power.

Zodzedrick

As the antagonist of the story, Zodzedrick’s main goal is to derail the community and lead them away from the uplifting goals that Treemonisha has for them. In her article, Rachel Lumsden explains that Zodzedrick establishes his dominance by controlling the key and dictating the “…harmonic action throughout the beginning of the quintet” (Lumsden 59). Zodzedrick firmly establishes the key of G Major with a perfect authentic cadence (PAC) in measure 12. A PAC is the chord progression V-I in root position. It is the most conclusive cadence there is, which is why Joplin’s choice to end Zodzedrick’s line with a PAC aids in the development of the character’s strong influence. Ned, Treemonisha’s father, tries to reroute the key Zodzedrick set by circling through numerous keys, but his efforts are futile. Up to this point, no character has been able to change the harmonic action that Zodzedrick has set.

Treemonisha’s entrance is the first that successfully changed the key. The meter shifts from 4/4 to ¾ and the key changes to Eb major, tonicizing the flat submediant of G major. Zodzedrick attempts to take control of the music again by briefly changing the current Eb major key that Treemonisha established, and moving to D minor after his entrance is m. 78. However, it is not as conclusive as his previous lines because he ends in an inverted imperfect authentic cadence (inverted IAC). That occurs when the chords go from V-I, but one or both of the chords are inverted. Out of the cadences, it is not as conclusive, which leaves the section that it concludes harmonically open. In short, Zodzedricks harmonic domination is waning (Lumsden 60).

Overall, Zodzedrick’s efforts to negatively influence the people in the town were not well orchestrated enough to be successful. Although Zodzedrick and his fellow conjurer, Luddud, triumph in belittling and capturing Treemonisha, they only prolonged their coming defeat. Despite being kidnapped and nearly tortured by the conjurers, Treemonisha convinces the town to forgive the two men. Her capacity for forgiveness is a testament to her well-deserved status as leader of the community. Zodzedrick still insists that he will not change his ways. His unwillingness to change further sets him apart from Treemonisha, the heroine of the story, and cements his villianist status.

Remus

As stated in the article Remus is Treemonisha’s friend/ pupil. Due to the love he has for Treemonisha he goes on a journey to find Treemonisha after he realizes she has been kidnapped. He also attempts to fight Zodzerick, but is stopped by Treemonisha because she hopes he will change. The closeness between Treemonisha and Remus is quite evident in the play and throughout the music. This is shown by them singing phrases together such as “Hope he’ll stay away from here always”. Unlike Zodzedrick, Remus’s notes do not clash with Treemonisha’s or the other characters. This is to do with the fact that Remus is kind of like the “hero”. He was used as another layer in the chord rather than the contrasting non-chord note like Zodzerick’s notes.