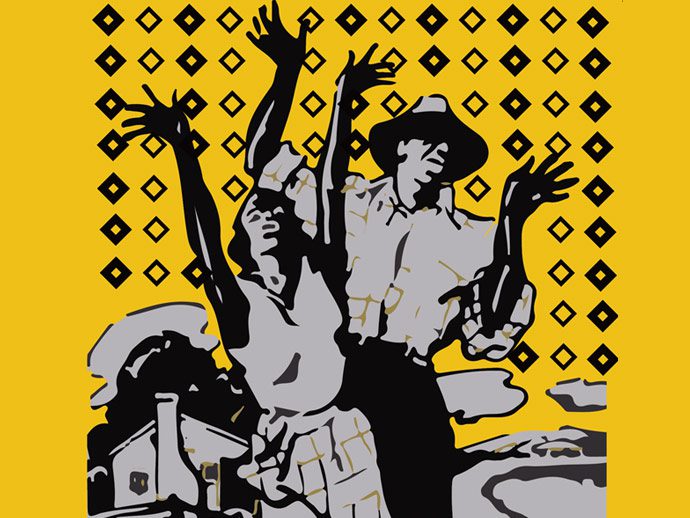

A Great Way of Performing? Or Another Spectacle for White People?

The Fisk Jubilee singers are one of the most famous examples of a group that brought attention to Negro Spirituals. But did the group’s formation lead to further commodification of the Black body and new commodification of the Negro spiritual?

Note, this is just my own opinion and analysis based on the information I’ve learned in this class and in African Diaspora and the World last year.

History of the Negro Spiritual

The Negro spiritual developed as a form of worship among the enslaved in the 18th century. Enslaved Africans were not allowed to worship in the same places as white people or even publicly. As a result, they created “invisible churches,” where enslaved people listened to chosen preachers without the master’s knowledge. Religion brought to enslaved people often emphasized obedience and phrased such that enslavement was justified in the eyes of God. However, worship in the invisible church did not center around obedience. Worship was also different in the invisible church in that West African styles of praise (such as dancing and music) could survive, as they were banned by the masters.

Lyrics for the music of the invisible church was created from Biblical stories and existing hymns. There was also instrumentation played with drums, the bones, and an instrument that is the ancestor of the banjo.

One of the structures of these spirituals was “call and response” which remains an integral part of worship to this day.

Earliest Commodification

In 1867, the first collection of Negro spirituals, Slave Songs of the United States was published. The collection contained 136 songs collected by Northern abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware. While I admire the fact that these spirituals were preserved, it is odd that the names of the enslaved people were never recorded. Instead, the three abolitionists (note, being an abolitionist and a white supremacist are not mutually exclusive) made a profit and get all the credit for work they did not create. While, I’ll admit, it would be hard for an African American, especially an enslaved person to publish anything, their names could have been recorded and they could have received a a cut of the profits, as enslavement was illegal at the time of publishing. The publishing of this book, especially by white Northern abolitionists, makes it seem part of an agenda. This comes across as “Look! Enslaved people have their own culture too! Isn’t it weird to enslave them?”

White Curiosity = Money for School

Okay, okay, maybe I’m being a little too cynical with this heading title. However, I am now going to talk about the commodification of the Negro spiritual when it came to the Fisk Jubilee singers.

The group was started in 1871 by George L. White, the treasurer and music director at Fisk University. He formed the nine-student choral ensemble on tour to raise money for the school. On the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ own website, there is the following statement:

“The first concerts were in small towns. Surprise, curiosity, and some hostility were the early audience response to these young black singers who did not perform in the traditional ‘minstrel fashion.'”

On the website, it never says if the students willingly participated in the group (although, nowadays, participation is voluntary). Were the singers forced to participate? The power dynamic between a white school administrator and a Black student would have been greater back then, only 7 years after emancipation. Did George L. White know that the singers would attract attention for being unusual at the time? It just seems a little odd to me. However, I do appreciate that George L. White did not make the singers perform in “minstrel fashion,” which was the only way Black performers could break into the industry at the time.

The Jubilee Singers did well. They performed for the president, Ulysses S. Grant, at the World Peace Festival in Boston, and toured around Europe. They raised enough money to construct Fisk University’s first permanent structure, which is designated a National Historic Landmark and so aptly named Jubilee Hall.

The Final Verdict

On one hand, it is amazing that an art form that was essential to the culture of enslaved Black people was preserved, and that many of these recorded spirituals were recorded and still performed today. Unfortunately, though, on the other hand, it is a testament to how often African Americans were (and still continue to be) exploited.

Your Opinion?

I’m curious to know how you feel about the commodification of the Negro spiritual. Leave a comment down below!

Works Cited:

“Our History.” Fisk Jubilee Singers, December 7, 2017. http://fiskjubileesingers.org/about-the-singers/our-history/.

Burnim, Mellonee V., and Portia K. Maultsby. African American Music an Introduction. New York u.a.: Routledge, 2015.