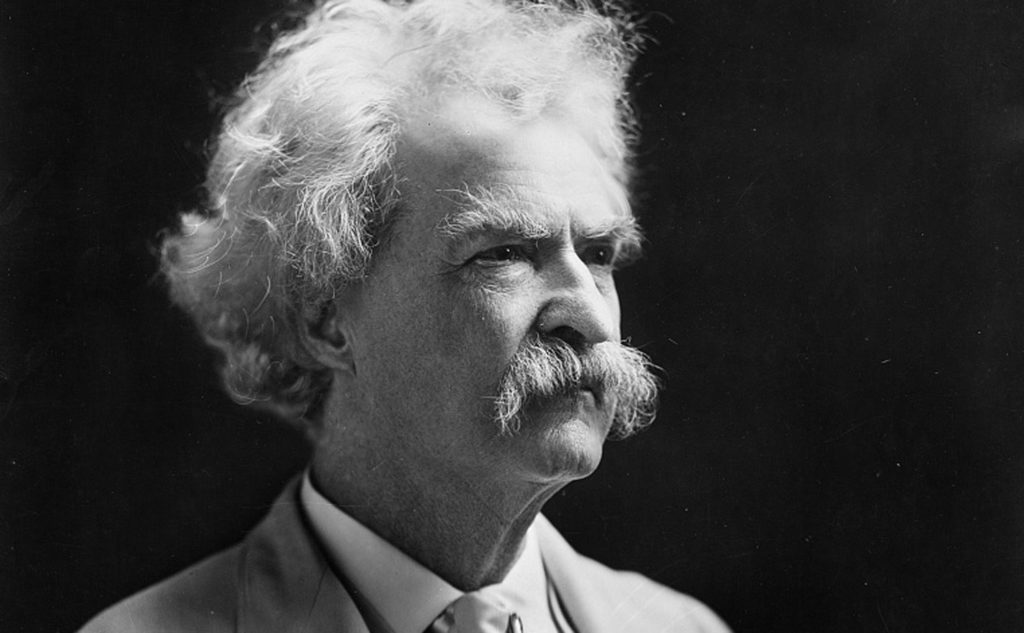

Before you say anything, I understand how you may be confused. On a site about black music scholars, why I am beginning my post with a picture of a white man? The truth is, as it always will be, the history of black people is connected to that of the white man, and this same ruling applies to The Old South Quartette, a musical group that started under Miller’s authority.

Though I will attempt to focus my blog solely on The Old South Quartette, I will not deny that their history is heavily interlaced with that of Miller’s, so the full history of the quartet and is currently not well-known, and probably never will be further obscured.

Origins & Influences

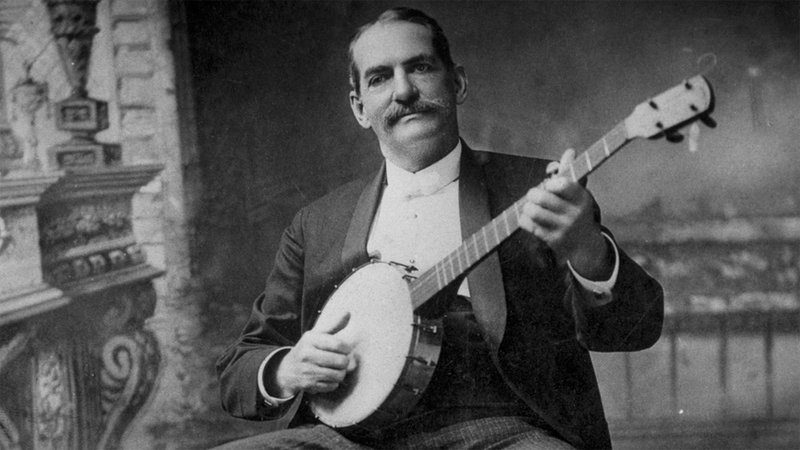

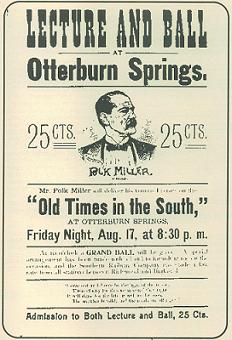

As I said before, the beginnings of the quartet begin with Miller, son of a slave master, who loved African-American music. He loved to play the banjo for his family, which was considered a black instrument at the time, and his family was fond of his music. He decided to delve into his interests full-time, embarking on several extensive tours in the South. Miller did not perform minstrel shows, but sometimes he did refer to himself as “The Old Virginia Plantation Negro,” and performed Negro spirituals and folk songs. Joel Chandler Harris, the author of Uncle Remus, was reportedly very impressed with Miller’s banjo skills, writing in the Atlanta Consortium, “when Polk Miller plays, you may look for a live nigger to jump out of his banjo.”

Another supporter, which came as a surprise to me, was Mark Twain, who found Miller’s sketches to be thoroughly entertaining and commended his storytelling abilities.

The original quartet Miller had gathered together were comprised of boys he had found singing on street corners. These boys followed him wherever his acts took him, including New York, Baltimore, and some exclusive social clubs, their shows usually lasting around two hours. Though many found their singing to be “uncultured,” it was, nevertheless, sweet, and caused heartfelt emotions due to harmonies (which were, contrastingly, found to be unequal to that of a professional singer). People from all over would come to see their performance, even paying up to 50 cents, which was a relatively high price at the time.

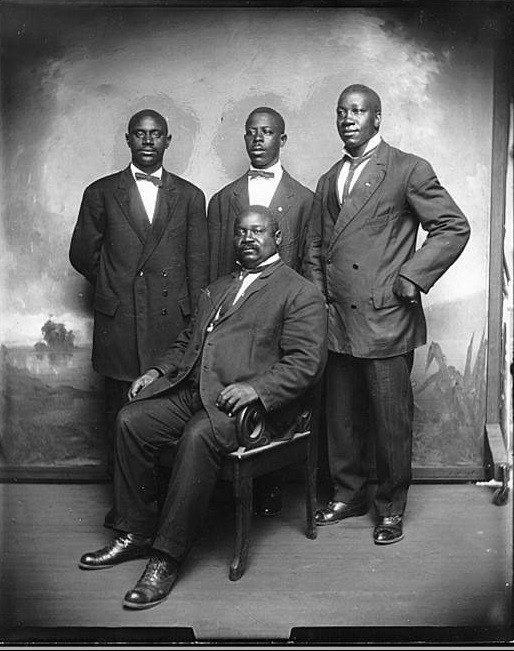

The quartet was joined by Col. Tom Booker around the early 1900s, a storyteller (pictured center in a chair), who joined Miller in his program “Two Old Confederates in Old Times Down South.” His name, as well as James L. Stamper and Randall Graves, have been the only names recovered from having participated in the quartet for some time. However, it is important to note that a total of twenty people had sung in Miller’s quartet. Miller and the quartet eventually parted ways in 1911, after it began to be too dangerous to travel from to show, and the story culminates with Miller’s death two years later.

Elements

Polyrhythm

Polyrhythms are several contrasting rhythms played or sung simultaneously. Quartets employed this style in order to add additional harmonic value and produce rhythmic variety. Quartets heavily focused on this aspect of music, along with lyrical content and context, to create their songs.

Grace note

A grace note is a short ornamental note performed as an embellishment before the principal pitch. It is indicated by a slash through the stem of the note. The grace note is used to add decoration or an “ornament” to the note being sung, to add a variety of expressions.

Strophic

A strophic is a song form in which a single melody is repeated with a different set of lyrics for each stanza. It is composed of a short or long phrase call-and-response, a combination of Western Europe and And African derived musical traditions. The strophic forms follow the forms of many folk songs.

Influence On Music

Though Miller traveled with black men, he was not one for racial equality. His views aligned with those of the Confederacy, even making his quartet sing a Confederate marching song named “The Bonnie Blue Flag.” In other words, he glorified black music, yet refused them their civil rights. With that being said, Miller is credited for preserving the music of the black culture, its nostalgia, and integrating black and white voices, an act which was virtually unheard of during that time.

Though I understand the origin of this accreditation, I am very hesitant to accept Miller as any type of revolutionary. Perhaps this is due to what I know of him, whether it is his stance on African-Americans, his desire to continue slavery, his alliance with the Confederacy. But most likely, I believe it is because there is so much known on Miller, but little known about the members of the quartet. Even with the names provided, their association was only with Miller, and no biographical context was given on any person. How specifically those members, and the rest of the twenty members that traveled with Miller, contributed to the quartet and its success is virtually unknown.

To conclude, I see Miller more as a glorifier than I do a contributor. But my opinion will not combat the many people who believe Miller contributed greatly to the integration in music and furthermore.