An Introduction to the Legendary Icon

Muddy Waters is considered to be one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century in terms of the popular culture of music. This blues musician forever changed the way poplar music was thought about and exposed to a nation and the world a new type of music, which was blues.

Blues is often mistaken for being a sad type of music. The foundation and origin of blues is built on the hardships and struggles about the African-American experience in the South, and the subject matter of blues musicians often included cotton fields and sharecropping. While blues music was born of the sad and miserable experiences of black people, but the songs were meant to tell black folks to rise above their circumstances and be hopeful rather than just stay in the state/place that they were in. This is what Muddy’s music was about to many people. His songs spoke about real life experiences but also spoke of a way to get out of the situation that one is in to better yourself.

Not only was Muddy Waters one of the leading faces for blues music, but he completely helped contribute to the changed music science of American and western music culture.

Methodology

For this research project on Muddy Waters, I used 7 different scholarly sources to find information about the life and career of the legendary blues musician, Muddy Waters. These scholarly sources came from different databases, scholarly journals, articles, and sections of books. Each of these sources offered information and perspective about Muddy’s life and career and how much of an influence he had on blues music and The British Invasion. I learned a great deal about the history behind blues music in general and the extensive research that has been done on the genre.

Early Life & Background, & Career

Muddy Waters was born McKinley Morganfield on April 4, 1913 on Stovall Plantatation in Clarksdale, Mississippi. This was right in the rich region of the Mississippi Delta. Muddy’s mother died shortly after he was born, so he was raised by his grandmother. Muddy earned his nickname “Muddy” because as a child he would often be seen playing in a muddy puddle near Dear Creek, which was close o where he lived.

As a child, Muddy loved being in the care of his grandmother and found comfort in the music of his church. By the time Muddy was 17, Muddy had bought his first guitar. Prior to officially becoming a full time musician, Muddy worked as a sharecropper. Like many African-Americans in the rural South, Muddy faced extreme amount of racism and discrimination. With Jim Crow being the way of life in the South, many black people felt that they would be forever stuck in a state of oppression if they did not leave.

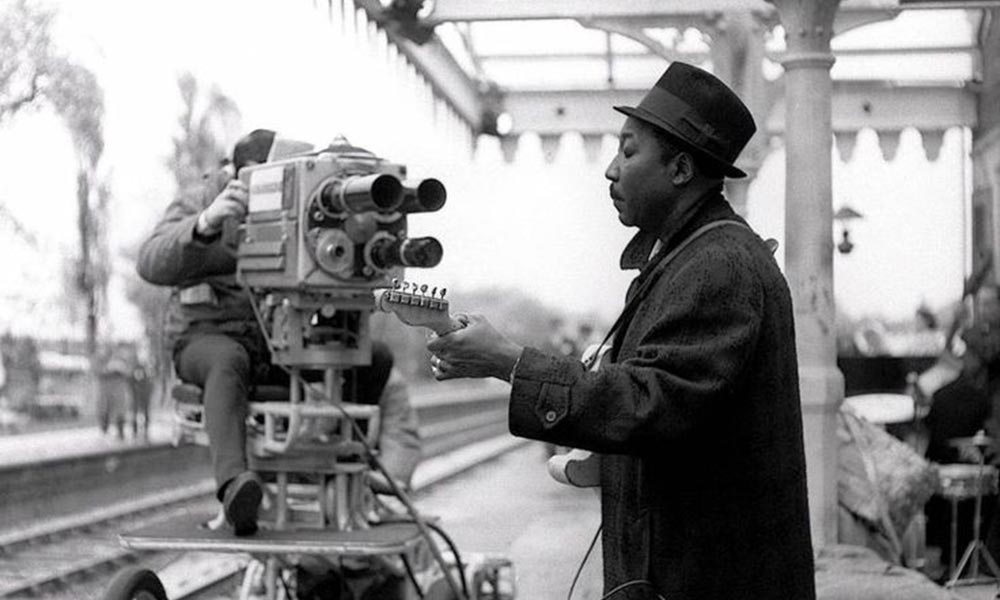

Muddy’s hard luck soon began to change when he met a Jewish man from the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax, in 1941. Lomax was on a tour of the Mississippi Delta recording and interviewing country blues musicians because the Library of Congress did not want to lose this history of music or culture. Muddy recorded some of his first songs for the first time with Lomax.

The Success Years of Muddy Waters

In 1943, Muddy left his grandmother in the Mississippi Delta and moved up North to the big city life of Chicago, Illinois. Just like many other African-Americans during this time after the end of World War II, there was little economic opportunities and social mobility for black people. So, many black people migrated up North to the cities looking for job opportunities in pursuit of a better life.

When Muddy first came to Chicago, he only had a suit of clothes and his guitar. He initially could not find work as a musician, so he worked grueling jobs in the factories of Chicago and drove trucks as a delivery man. On the side, he would perform in the black nightclubs of Chicago. Many African-Americans who had migrated to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta found comfort and solace in the lyrics of blues musicians like Muddy. Muddy could relate to them because he himself was trying to acclimate to a new environment of being in the city while also maintaining his roots and foundation of being a southern Delta man.

Much of Muddy’s music dealt with movement and mobility. Some of the lyrics to his songs referred to the trains that left the South and went up North to places like Chicago to Grand Central Station. To many African-Americans, the true was symbolic because it represented a way and path to life away from the South. It represented freedom and the ability to both figuratively and literally leave the slave-like way of life in the South.

While in the South, Muddy helped develop a new style of blues that was different from the country blues and Mississippi blues. The style that he popularized was Chicago blues (also known as urban blues). During this time, Muddy had formed a band with bandmates with Little Walter Jacobs on harmonica, Jimmy Rogers on guitar, Elgin Evans on drums, and Otis Spann on the piano. This group is one of the music acclaimed blues groups of all time. They produced several major hits with Alan Lomax’s record company Chess Records.

It was a big deal for black artists to be able to record music and have their name on the songs to be given credit for it because many black musicians were either not allowed to record music or if they did, their name was not accompanied with the song, so the artist of the song would be unknown. In 1948, there was a ban that prevented the recording and release of new songs in Chicago. However, Muddy and his band ignored this and continued to make music. They produced many popular songs as their recordings were still broadcast and played on radio stations and caught the ears and attention of many black and white listeners alike. This showed that though segregation still existed in Chicago, black musicians still had the power and ability to attract white listeners and could still use music as a way to create opportunities for themselves.

Muddy and his band often sang songs about African-Americans traditions and beliefs, such as hoodoo. There were several hit songs that they released, such as 1950’s hit songs “Rollin’ Stone” and “Louisiana Blues”, 1954’s hit song “I’m Your Hootchie Coochie Man”, and 1955’s hit song “Mannish Boy.”

Later Life & Career

By 1958, Muddy’s music popularity and fame started to decline as new music genres such as rhythm and blues, soul, and rock and roll were starting to become increasingly popular among younger audiences and teenagers. Artists such as Chuck Barry, Little Richard, and James Brown were becoming nationwide phenomenons, but little credit and appreciation for blues musicians like Muddy Waters was talked about. Rock and roll used the electric guitar and slide guitar style that was inspired by blues. While blues musicians may not have gotten a lot of appreciation from America at the end of 1950s, they unexpectedly did across the pond in the United Kingdom.

in 1958, Muddy traveled with fellow bandmate Otis Spann to England. Muddy performed performances in front of large white audiences in many places all around the United Kingdom, such as London, England, Manchester, England, and Leeds, England. The people of England had long been accustomed to the sound of more traditional folk musicians and traditional jazz musicians. However, they were not quite prepared for the loud electric guitar sound of Muddy and his slide guitar playing on his electric guitar, along with an amplifier. Nonetheless, while older listeners felt alienated from this sound of music, quite a few younger listeners were inspired by Muddy’s sound and wanted to develop a more modern, electric guitar style. These young listeners would form famous British rock bands such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Cream, and Fleetwood Mac, which are groups central to The British Invasion.

Throughout the 1960s British Invasion, Muddy’s popularity began to rise among white listeners and his name came to be more respected. By the 1970s, Muddy had earned several Grammy Awards and released several very successful and critically acclaimed albums.

On April 30, 1983, Muddy died of heart failure related to cancer at the age of 70 at his home in Westmont, Illinois. He was buried next to his wife Geneva at Restvale Cemetery.

Response to Muddy Waters

Divisiveness Among African-Americans

After WWII, many African-Americans left the South to go North to big cities such as Chicago, New York, and Detroit looking for better opportunities and treatment this was known as the Great Migration; Muddy’s music appealed to them because he himself was from the South and was learning how to adjust to living in the North in the city while still remaining the core aspect of his identity, which was that of a Delta bluesman.

However, not all black people in the North liked blues music; there was a newly burgeoning black middle class that had adjusted and acclimated with northern city life and listened to more ‘sophisticated’ and ‘classy’ forms of music such as jazz.

Muddy was considered a “throwback” to some black Americans. While Muddy was very innovative and influential for rock and roll music, many African-Americans thought he was “too country” for urban black America in the North. For some black people, Waters was a reminder of what had happened to black people generations ago; things that had been left behind (such as sharecropping, slavery, little economic opportunity/social mobility). Black people felt that the black race had progressed and moved past these downtrodden experiences.

However, black people still living in the South loved Muddy because he was someone who came from the South and made it. He became successful and made the experiences of black people living in the South mainstream to the mainstream American population. To them, this was revolutionary because often, in many forms of music, such as jazz and rhythm and blues, black people believed that they were advancing and no longer had to focus or worry about sharecropping, the white sharecropping master, or being poor. Since black people were becoming more educated and musicians more properly trained, and a new black middle class and suburban black America was forming. It was time for the black race as a whole to move forward instead of keep talking about “downtrodden” topics like the blues did.

Praise and Appreciation from White Americans & Europeans

White people have always been curious about blues. Blues was created as early as the 1890s right after the Civil War ended. Black people were free and liberated, but still faced mass amounts of systematic and societal racist. Black people started singing about their experiences and life in the South. Many of the songs were undocumented and not recorded.

White people from the North, particularly Alan Lomax, went down to the South and interviewed different blues singers and recorded their songs. This helped popularize blues music beyond just blacks living in the South

While white Americans weren’t initially listening to blues music in large numbers in the 1940s and 1950s, many Europeans were. In the 1960s, there was a folk music revival where many white Europeans, such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Eric Clapton were heavily influenced by Muddy Waters and other blues artists. These groups saying that they were heavily influenced by Muddy and singing in a similar music style to him made blues music popular among white teenagers and young adults during the 1960s. This made Muddy Waters an icon and very popular/famous musician. If it were not for the songs of Muddy Waters and other blues musicians, rock and roll would not exist and The British Invasion would never have happened.

It is interesting to observe how it was mainly white people that made Muddy Waters a cultural phenomenon. This was a group of people who were not from the same background as Muddy Waters at all or understood the racial and societal experiences that he did. However, they greatly respected and appreciated his music and the blues genre of music as a whole. It is kind of ironic how one would expect Muddy’s own race to support him and understand the experiences of black Americans because whether you live in the South, North, Midwest, or West, racism exist everyone. However, this is not the case since it was Muddy’s appeal to large white audiences and fans that gained him respectability and much fame in the music industry.

The Honors & Legacy of Muddy Waters

Honors & Awards

Muddy Waters has received many honors and accolades for his legendary music career and contribution to both blues music and popular music. He received 6 Grammy Awards for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording between 1972 and 1980:

1972 Grammy Award for the album They Call Me Muddy Waters

1973 Grammy Award for the album The London Muddy Waters Session

1975 Grammy Award for the album The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album

1978 Grammy Award for the album Hard Again

1979 Grammy Award for the album I’m Ready

1980 Grammy Award for Muddy “Mississippi” Waters Live

1992 Honoree of the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame listed four of Muddy’s songs that are on the 500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll List:

Rollin’ Stone (1950)

Hootchie Coochie Man (1954)

Mannish Boy (1955)

Got My Mojo Working (1957)

Muddy Waters has also been inducted into several prestigious Hall of Fame’s:

1980 induction into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame

1987 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

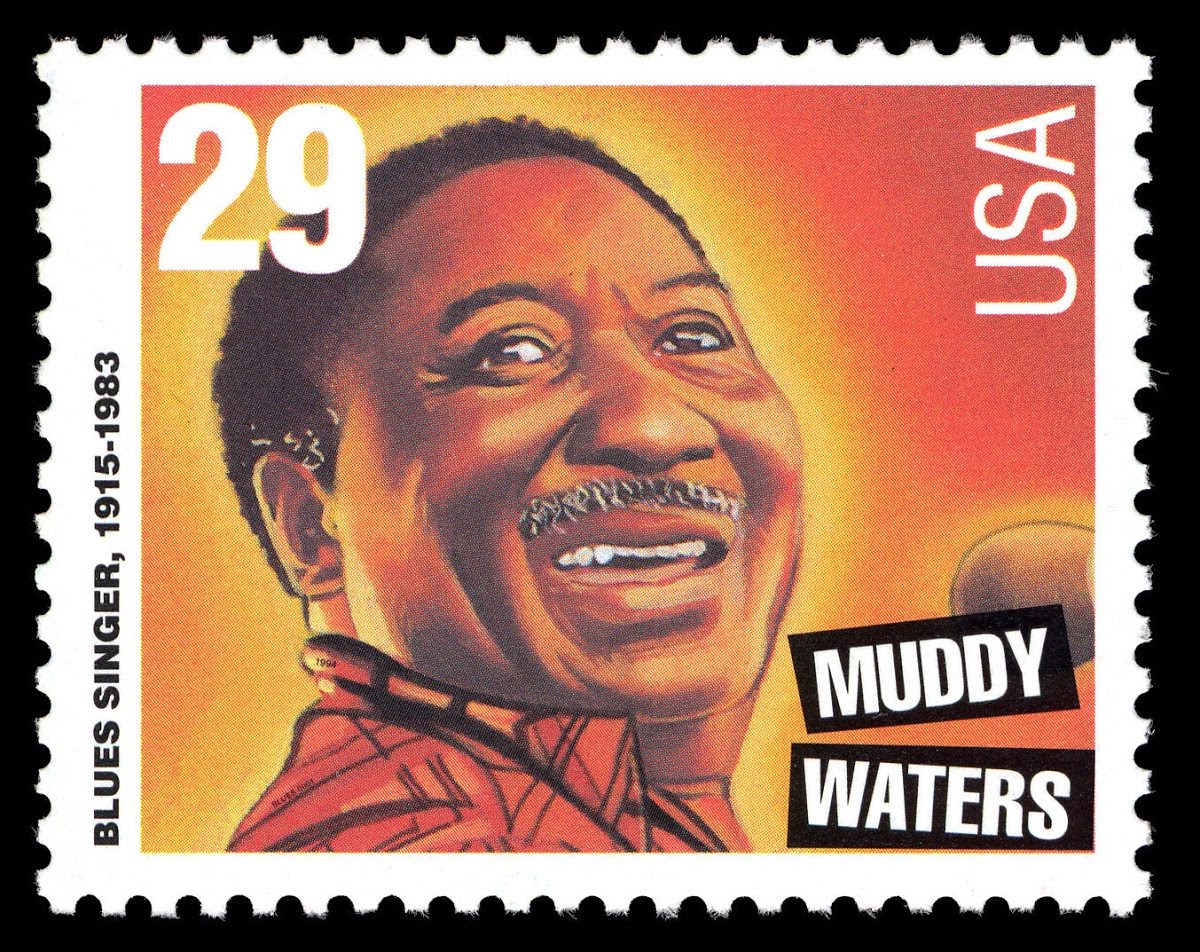

1994 Honors of a U.S. Postal Service Commemorative Stamp

A few of Muddy’s songs are included in Rolling Stone magazine’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time List:

I’m a Hootchie Coochie Man (#226 on the list); this song was also awarded a Grammy Hall of Fame Award; this song is also preserved in the U.S. Library of Congress National Recording Registry

Mannish Boy (#230 on the list); this song was also inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame’s “Classics of Blues Recordings” cateogry

Rollin’ Stone (#459 on the list); this song was also awarded a Grammy Hall of Fame Award

Legacy

Muddy Waters became one of the most influential cultural music icons of the 20th Century. His influence has influenced so many musicians across all different genres, from soul to rhythm and blues to rock and roll. He overcame so many challenges in life, mainly racism, and criticism of his music from members of the black community. However, he kept recording blues music and he was passionate about it. It eventually led him to being one of the main influences and central figures of perhaps one of the greatest musical phenomenons in history, The British Invasion. The British Invasion is one of the key events that created modern, mainstream, and popular music in America. It is safe to say that if it wasn’t for the Muddy Waters and other blues musicians (such as Howlin’ Wolf), the British Invasion would never have happened. This leads to another conclusion which is that popular music that we know today would possibly not be as we know it if it weren’t for Muddy Waters and blues.

Muddy’s legacy is still remembered today since a nice, huge mural has been draw of him that is on a high building in Chicago. Muddy’s sons continue to perform blues music during different shows, performances, and concerts.

Bibliography

Cardany, Audrey Berger. “Muddy Waters: His Life and Music.” General Music Today, vol. 31, no. 3, Apr. 2018, pp. 73–79. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1177/1048371318756626.

Cowley, John. “Really the ‘Walking Blues’: Son House, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and the Development of a Traditional Blues.” Popular Music, vol. 1, 1981, pp. 57–72. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/853243.

Ferris, William. “Blue Roots and Development.” The Black Perspective in Music, vol. 2, no. 2, 1974, pp. 122–127. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1214229.

First, David. “It’s for You: Muddy Waters’s ‘Long Distance Call’ and How Delta Blues Re-Set the Controls for the Heart of the Earth.” Leonardo Music Journal, vol. 22, 2012, pp. 79–84., www.jstor.org/stable/23343815.

Goven, Jennifer (2005) “From the Delta to Chicago: Muddy Waters’ Downhome Blues and the Shaping of African-American Urban Identity in Post World War II Chicago,” McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol9/iss1/8

Hellmann, John M. “‘I’m a Monkey’: The Influence of the Black American Blues Argot on the Rolling Stones.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 86, no. 342, 1973, pp. 367–373. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/539360.

“Redefining the Music Industry: Independent Music in Chicago, 1948–1953.” The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900-1967, by Amy Absher, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2014, pp. 82–97. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3znzb4.7.