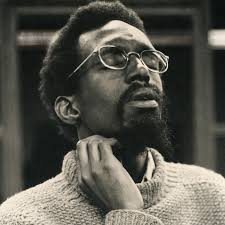

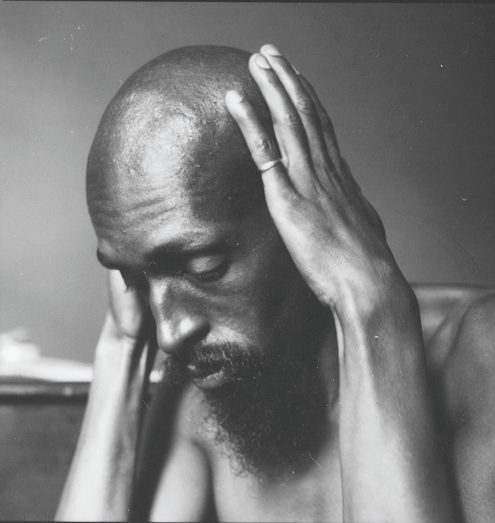

“What I am trying to achieve is to be what I am to the fullest...Black to the fullest, a musician to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.” - Julius Eastman, 1976

From Humble Beginnings..The Origins of Julius Eastman

- Julius Eastman was born on October 27th, 1940 in Ithaca, New York. He was born into a small family and grew up with his mother, Frances Eastman and his younger brother, Gerry Eastman.

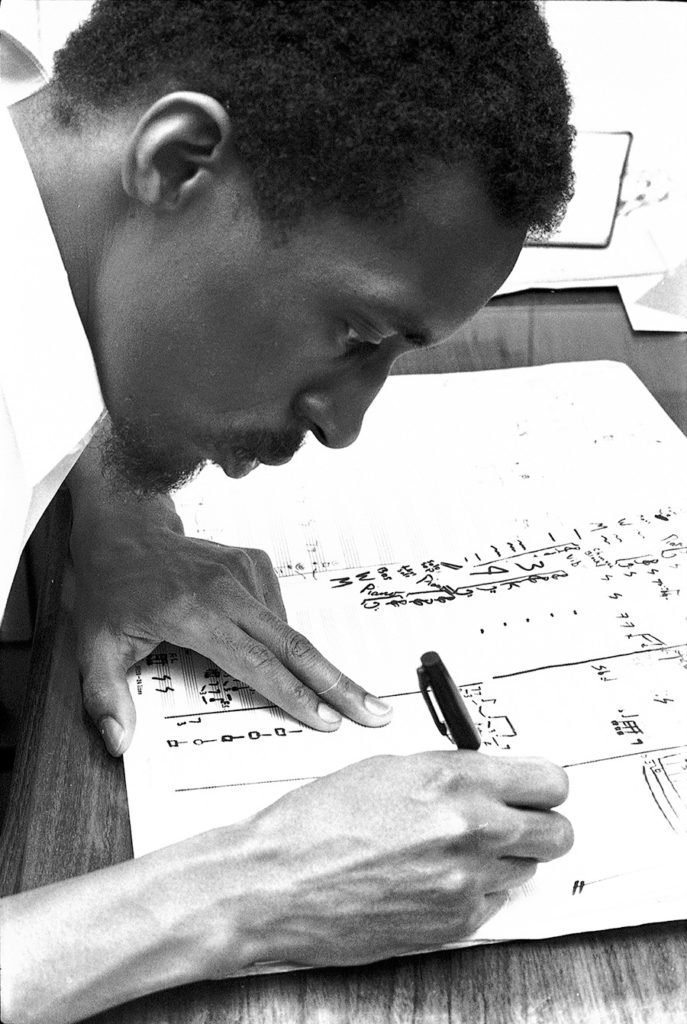

- At a very early age, Julius Eastman showed great musical potential and his mother noticed it. Thus, despite not having very much money, she enrolled him into music classes to facilitate and encourage his progress as a musician. Eventually, Eastman attended Ithaca College to study music and later studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia to continue his studies. It was at the Curtis Institute of Music where Eastman discovered his passion for composition.

- While at the conservatory, Eastman always expanded on his musical abilities and explored the great depths of his talent by expounding on his vocal abilities as a bass.

Eastman’s first professional performances after college were in piano, but eventually, he would perform both instrumentally and he would use his powerful bass voice. Furthermore, his compositions would gain recognition in New York and across the East coast and would be performed by himself or with other musical groups.

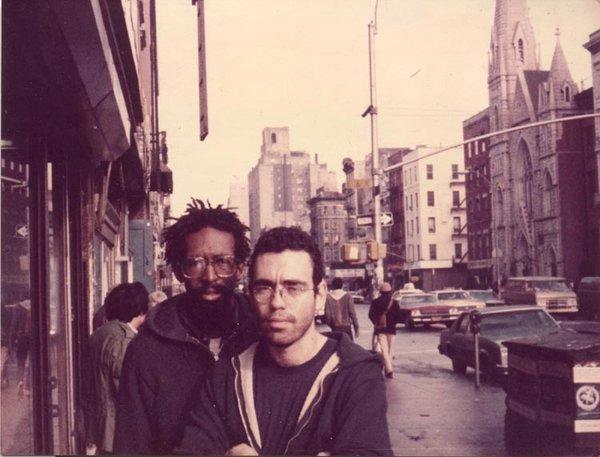

The 70s: Eastman’s Life in the New York Music Scene

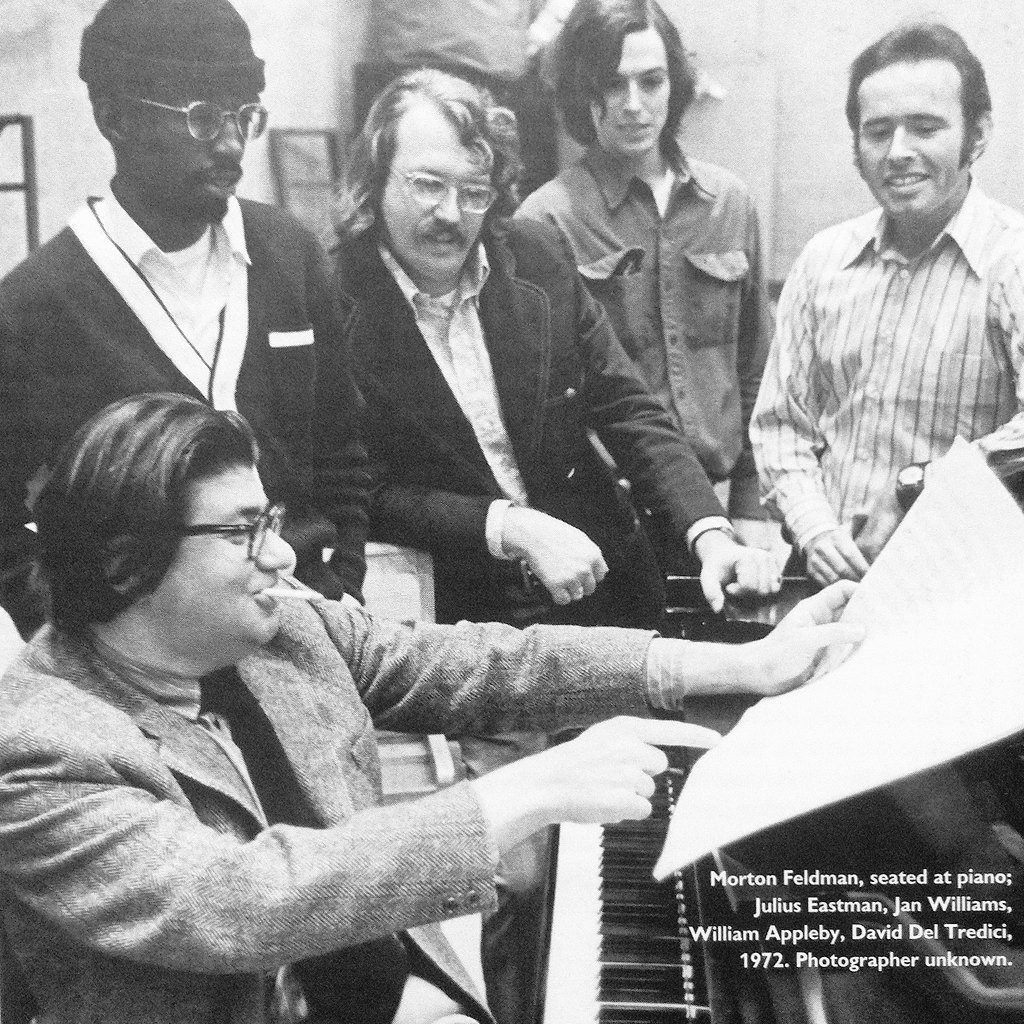

- During this time period, New York City especially was very open to unique and arguably, a bit strange, musical innovations and genres. Minimalistic music was starting to gain popularity amongst the New York music scene and Eastman’s music fit perfectly into this genre.

- Most minimalist music during this time was created by white composers and it is those compositions that seemed to dominate the genre for quite some time. Despite this, Eastman still found success on the East Coast but ultimately, he did not receive the acclaim he deserved as a minimalist and classical composer until after his death.

- Julius Eastman first found success with his song, “Stay On It” released in 1973.

Julius Eatman’s compositions were quite radical in orchestration, in lyrics and in concept; and unlike white minimalist composers of the time, Julius Eastman’s compositions always came with very clear commentary on the socio-political climate of the time period.

- For example, his works Evil Nigger, Crazy Nigger , Prelude to The holy presence of Joan d’Arc, and Gay Guerilla, Eastman makes a very clear commentary on race relations and queerness in the world around him through bold orchestration.

- At certain points in Eastman’s career however, he paid a great price for his radicalism. For example, in the early 70s, Eastman was given the opportunity to teach music theory and composition at a university in Buffalo, New York but he lost the job after giving a very radical performance that included nudity and expressed themes of queerness that were shunned during the time period.

The End?

- Julius Eastman passed away on May 28th, 1990 in Buffalo, New York. Towards the end of his life, Eastman struggled with drugs, homelessness and his finances, and in the midst of this, most of his music was lost.

- When Eastman first passed away, none of his friends, or those who had been in contact with him in his later years, was notified. One of his closest friends and colleague, Kyle Gann, discovered he had passed eight months after his death and wrote him a formal obituary, summarizing his life and legacy and recognizing him for his work.

- Upon finding out about his death, many of Eastman’s friends and close colleagues who performed with him in the 70s and 80s attempted to maintain his legacy and keep his music alive by searching for his lost music, interviews and compositions, but it would be years before the majority of his currently known-work was restored.

Posthumus Success

- In the mid-2000s, a number of contemporary conductors began to find out about Julius Eastman’s music and began performing his compositions again. During this time, many students in music programs at different universities began to take interest in his work and researched it further.

- The person most responsible for revitalizing Julius Eastman’s career postmuthusly is Mary Jane Leach who found a number of his scores and released them to her website. Eventually, she wrote a autobiographical paper on Eastman’s life titled “Gay Guerilla.” After his own song of the same name.

- After this, Julius Eastman’s name gained newfound popularity and many scholars in music academia and in the world in general researched his life and career much more deeply.

Bibliography

Als, Hilton. “The Genius and the Tragedy of Julius Eastman.” The New Yorker, The New

Yorker, 11 Jan. 2018, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/22/the-genius-and-the-tragedy-of-julius-eastman.

Cooper, Michael. “28 Years After His Death, a Composer Gets a Publishing Deal.” The New

York Times, The New York Times, 21 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/02/21/arts/music/julius-eastman-schirmer.html.

Hanson-Dvoracek, Andrew. “Julius Eastman ‘s 1980 Residency at Northwestern University.”

University of Iowa, Iowa Research Online, 2011, pp. 1–115.

BOYD, HERB. “Classical Avant-Garde Composer Julius Eastman.” New York Amsterdam

News, vol. 109, no. 9, 2018.

Gaines, Malik. “Julius Eastman.” Artforum International, vol. 56, no. 8, 2018, pp. 53–58.

“Julius Eastman.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Mar. 2019,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Eastman.

Leach, Mary Jane. “The Julius Eastman Project.” Mary Jane Leach > Julius Eastman Scores,

2015, www.mjleach.com/eastman.htm.

O’Brien, Kerry. “The World Catches up to Iconoclastic Composer Julius Eastman.” Chicago

Reader, Chicago Reader, 3 Mar. 2019, www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/julius-eastman-frequency-festival-gay-guerrilla-composer-minimalist/Content?oid=41540539.

Schirmer, G. “Julius Eastman.” Claude Debussy – Long Biography – Music Sales Classical,

www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/short-bio/Julius-Eastman.

Shatz, Adam. “Bad Boy from Buffalo.” The New York Review of Books, The New York Review

of Books, 10 May 2018,

www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/05/10/julius-eastman-bad-boy-buffalo/.

“Spinning on Air.” Performance by David Garland, episode Julius Eastman In His Own Voice,

1984.

Wbur. “Resurrecting The Political, Avant-Garde Music Of Julius Eastman.” WBUR, WBUR, 5

Feb. 2018, www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2018/02/05/julius-eastman-music.