Menu

Worlds Away: Decostructing the Racial and Political Identity of Jimi Hendrix

Previous

Next

Research Methodology

Jimi Hendrix is remembered as much for the aura of mystery that surrounds his “Electric Gypsy” character as he is for his music and legendary guitar-playing. Most biographies, which sanctify Hendrix’ abilities on the guitar and his unprecedented rock and roll performance styles, fail to encompass Hendrix as a black man with opinions and feelings informed by the plight of black Americans during the 1960s.

This analysis — like Hendrix himself — is multifaceted. Different interpretations of his music are considered, as the art and personal life of an artist are often inseparable. Because he was a pop culture icon during a time when contemporary media coverage of pop culture was burgeoning, there are many first-hand accounts from Hendrix that are available online and in print. It is most enlightening to hear what Hendrix has to say about his identity in his own word. However, it was uncommon of him to comment on the political and racial climate of the day. Hendrix personal and projected construction of self and society may well be hidden in these silences.

Thesis

Jimi Hendrix’ commercial success as an artist was dependent on him embracing whiteness and appealing to white audiences by remaining separate from the politics of the racially tumultuous 1960s.

Early Life and Introduction

Jimi Hendrix was born Johnny Allen Hendrix on November 27, 1942, in Seattle, Washington. He did not know his mother well and was raised by his father and other relatives (“Jimmy Hendrix”). Hendrix went to racially-integrated schools within a largely integrated Northwestern city. As a result, he developed a racial identity different from many black artists of the American South and Northeast, who would later galvanize the Black Power Movement.

Jimi Hendrix’ father encouraged his interest in music by buying him an acoustic guitar at the age of 16. Hendrix was a virtuoso but had very little formal training in guitar. Much of what he learned he learned either by listening to records or by attending shows. As a youth he often would talk to blues musicians after shows and have them teach him their tricks, but he had little of the sort of training many guitarists get today. Still, within ten years, he was able to go from first picking up a guitar to becoming one of the world’s most heralded guitar players.

Three years after he started playing the guitar, Hendrix enlisted in the United States Army, where he served for two years as a paratrooper (“Jimi Hendrix”). After his honorable discharge, Hendrix came back to America and began touring on the Chitlin Circuit, a string of music venues in the South that were critical to supporting the early careers of artists like B.B. King, Solomon Burke, James Brown, and the Isley Brothers to name a few (Cross).

Hendrix was immediately popular as a guitarist in the rhythm and blues scene. He was such an outstanding guitar playing that he never had to look outside the music industry to make his living. However, he was not personally fulfilled as an artist, “I wanted my own scene, making my music, not playing the same riffs” (Fricke). Hendrix was often upstaging people he was hired to back up. After a while, he was not getting hired at all. When Hendrix decided to relocate to Greenwich Village, London, England his superstardom burgeoned.

Hendrix: The Musician and Performer

Hendrix’s musical career did not take off until he abandoned a career as a largely anonymous R&B sideman on the racially segregated Chitlin Circuit and began playing his music before largely white audiences in Greenwich Village, London, England. Greenwich is where Hendrix truly started getting support and recognition for his talents. Under the patronage of Linda Keith, girlfriend of Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, Hendrix found a manager and assembled a three-piece band, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames (Wenner).

By launching his career in England, Hendrix allowed himself to get some distance from the racial conflict in his own country. This distance allowed him to fully engross himself in his music. His debut album with The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Are You Experienced, received critical acclaim for its virtuosic guitar playing, first-rate songwriting, and eclectic psychedelic interpretations of blues, soul, and rock and blue.

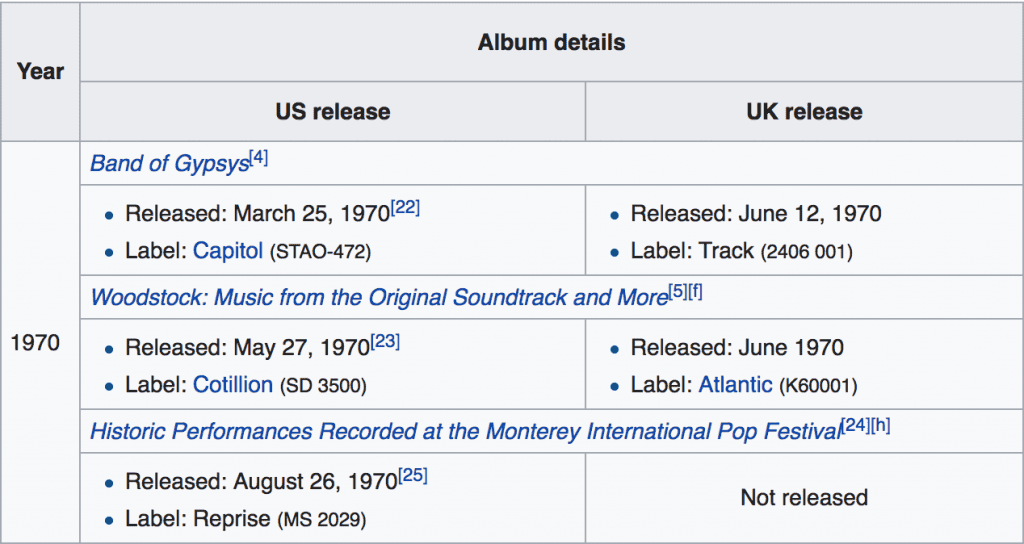

Hendrix recorded only three fully-conceived albums during his lifetime: Are You Experienced in 1967, Axis: Bold as Love in 1967, and Electric Ladyland in 1968 (“Jimi Hendrix”). The two albums after Are You Experienced introduced the kind of instrumental experimentation Hendrix would come to be known for. He pioneered the use of the recording studio as an instrument in itself to create an otherworldly aesthetic. He created new techniques in distortion, echo, and volume which are now hallmarks of rock and roll.

Hendrix’ experimentation on the guitar was completely revolutionary to white audiences who were not familiar with old blues players. There were other black artists who were equally as experimental on the guitar and who were regionally popular. It could be argued that Jimi Hendrix place in the history of rock and roll has been so dramaticized because of his willingness to step and exist in white worlds, “here after all was a Black artist who stepped way on the other side of America’s racial/musical/political divide at a time when lines were being drawn” (Tate). The Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Who, and Eric Clapton all praised his work. This popularity was in contrast to Hendrix’ near invisibility in black music circles: “In London and East Village he was The Man. In Harlem, he was the invisible man” (Tate).

Even his shows, which scandalized white audiences, were typical of popular black artists of the time. His theatrical performance style included unmistakably sexual movements, and tricks like playing the guitar with his tongue and behind his back (Wells). Most of his performances were under the influence of hard drugs like LSD and often ended with him lighting his guitar on fire or smashing it to pieces. He created a public image for himself that exuded swag, confidence, and a devil-can-do attitude.

Hendrix: The Black Man

Jimi Hendrix had an uneasy relationship to racial politics in the 1960s. He was playing in a racially integrated group with a largely white fan base at a time when the political context was pushing many young black activists in a more nationalist or separatist direction.

Jimi Hendrix was most popular at the height of the Vietnam War and the peak of the American Civil Rights Movement. Moreover, the 1960s were a time when black artists were thriving across various fields, from Ellison and Baldwin in literature, to Marian Anderson in classical music, to the Dance Theater of Harlem, among countless others. Unlike Hendrix, most of the black artists of the time used their platform to raise awareness of issues affecting Black Americans as a group.

Hendrix projected a conception of himself as an individual unaffected by the problems that affected the rest of his race. His relationship with the racial politics of the day are summarized in his quote from a July 1968 interview he gave to the United Kingdom newspaper Melody Maker, “I just want to do what I’m doing without getting involved in racial or political matters. I know I’m lucky that I can do that … lots of people can’t.” Moreover, when an underground newspaper Open City interviewed Hendrix before a 1967 concert in Los Angeles about the recent race riots in Detroit, Hendrix was cautious not to give any support for political violence or for much of any political viewpoint at all:

“Well, quite naturally, I don’t like to see houses being burnt. But I don’t have too much feeling for either side right now, because my bag is completely different. Quite naturally, a lot of things have happened to me. But don’t forget every human being on this earth is different. So how are you going to classify races by what they do? Sure, I get made when I hear people dying in wars of ghettos. Maybe I’ll have more to say later when I get more political” (Fricke).

Machine Gun is his most overt protest piece, although many people argue that his Woodstock performance of “The Star Spangled Banner” had elements that reflected black rage and was a clear indication that he claimed America as his country as much as any white person could. However, Machine Gun is a clear admonition of the futility and waste of war and of state repression of the civil rights and student protests of the 60s. Before every live performance, Jimi dedicated the song to soldiers fighting in Vietnam and domestically like Milwaukee and New York for example. His dedication to soldiers fighting domestically was an ironic one. It is clear that he acknowledged the struggle of black Americans, even if he did not identify with them himself.

Conclusion

When Jimi Hendrix did have a choice over how to express himself, he often preferred to have his guitar do the talking for him. Whether or not he was motivated more by, “his musical ambitions… [which] required white patronage and demanded he not be read as racially threatening or intimidating,” or by his initial and ongoing rejection by black audiences, Hendrix’ avoidance of the political is undeniable. His time in Harlem seems to have been particularly influential, as he related, “In the Village, people were more friendly than in Harlem where it’s all cold and mean. Your own people hurt you more. Anyway, I always wanted a more open and integrated sound” (Wenner). Undoubtedly, Hendrix carried that hurt throughout his short, explosive career.

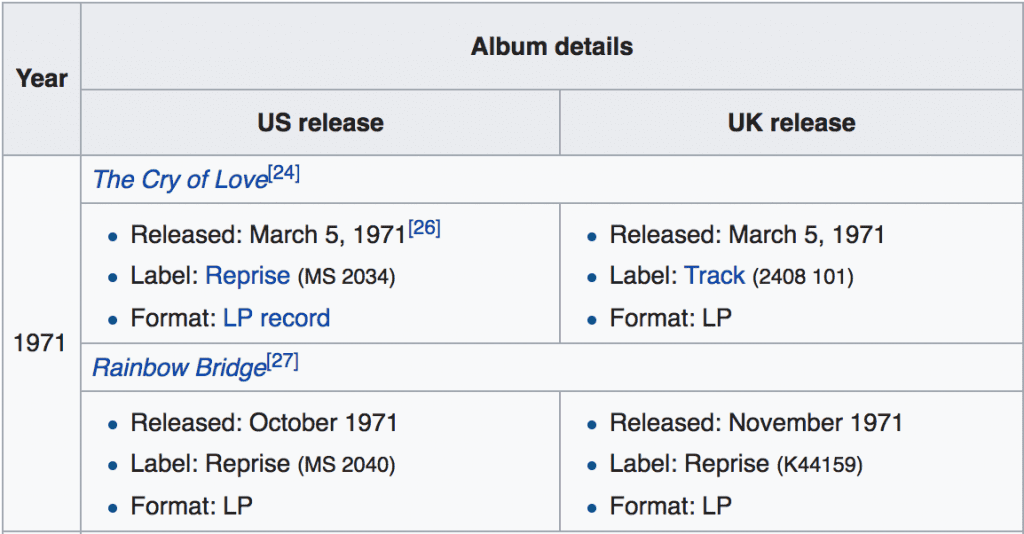

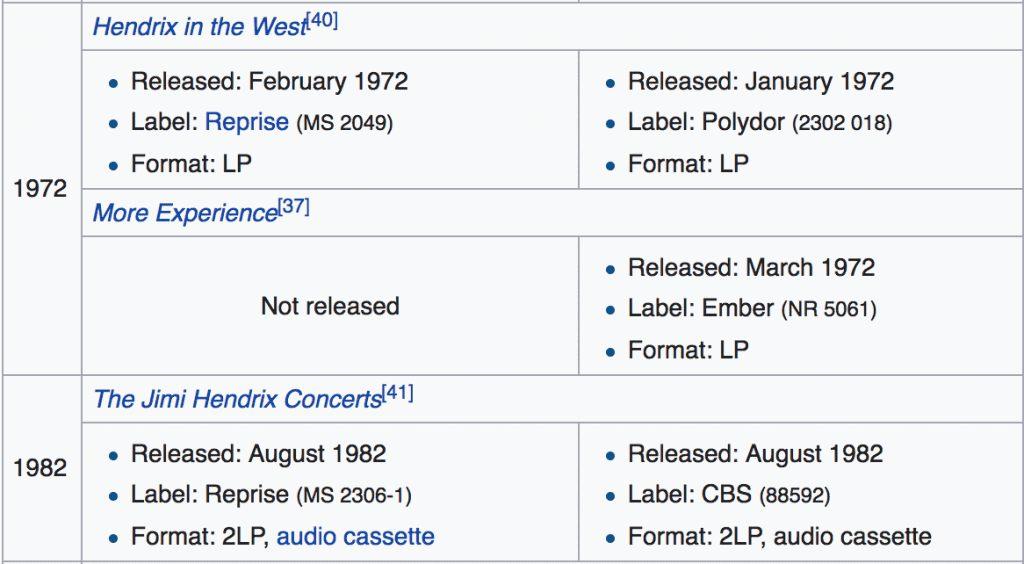

On September 18, 1970, Hendrix was found dead in London (“Jimi Hendrix”). His exhaustive lifestyle, excessive use of drugs, and massive fame caught up to him. In the years since and even today, posthumous releases and tours inspired by Hendrix’ music keep his legacy alive. Despite his short career, Jimi Hendrix remains an influence on guitarist everywhere. His pioneering work has left a lasting impact on all genres of music.

Discography

Posthumous Discography

Bibliography

Adams, Marcus K. “The Racialization of Jimi Hendrix.” Digital Commons @ EMU, Eastern Michigan University, 2007, commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=honors.

Clague, Mark. (2014) This Is America?: Jimi Hendrix’s Star Spangled Banner Journey as Psychedelic Citizenship. Journal of the Society for American Music 8:04, pages 435-478.

Cross, Charles R. Room Full of Mirrors: a Biography of Jimi Hendrix. Hachette Books, 2006.

Fricke, David. “Jimi Hendrix: The Man and the Music.” Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 6 Feb. 1992, www.rollingstone.com/music/features/jimi-the-man-and-the-music-19920206.

“Jimi Hendrix.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 28 Apr. 2017, www.biography.com/people/jimi-hendrix-9334756.

Tate, Greg. Midnight Lightning: Jimi Hendrix and the Black Experience. Verso, 2004.

Wells, Jeremy. “Blackness Scuzed: Jimi Hendrix’s Invisible Legacy in Heavy Metal.”Academia.edu, www.academia.edu/8659754/Blackness_Scuzed_Jimi_Hendrixs_Invisible_Legacy_in_Heavy_Metal.

Wenner, Jann S, and Baron Wolman. “Jimi Hendrix On Early Influences, ‘Axis’ and More.”Rolling Stone, Rolling Stone, 9 Mar. 1968, www.rollingstone.com/music/news/its-jimi-hendrix-from-1968-on-early-influences-axis-and-more-19680309.

Experience Hendrix: In His Own Words

"Music is stronger than politics. I feel sorry for the minorities, but I don't feel a part of one."

"Music doesn't lie. If there is something to be changed in this world, then it can only happen through music."

"I try to use music to move these people to act"

"When things get too heavy, just call me helium, the lightest known gas to man."

Previous slide

Next slide

More Information

www.rollingstone.com/music/features/jimi-the-man-and-the-music-19920206

commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=honors

www.biography.com/people/jimi-hendrix-9334756

www.rollingstone.com/music/news/its-jimi-hendrix-from-1968-on-early-influences-axis-and-more-19680309

Other Works by Author

Billy Taylor

November 29, 2017

No Comments

Billy Taylor, a pianist and composer who was also an eloquent spokesman and advocate for jazz as well as a familiar presence for many years on

Fisk Jubilee Singers

November 10, 2017

No Comments

Five years after Fisk University was founded, George L. White created a nine-member choral ensemble of students and took it on tour to earn

Jimi Hendrix: The Invisible Man of Rock and Roll

November 12, 2017

No Comments

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwIymq0iTsw[/embedyt] Research Methodology: First-hand accounts from Jimi himself, those who knew and worked with him, and critical interpretations of his music were used to

Spelman College Glee Club

November 30, 2017

No Comments

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0soOmx9Y2Ic[/embedyt] Like many HBCUs, Spelman College has a premiere music ensemble which carries on the negro spiritual tradition. The Spelman College Glee Club has

Esperanza Spalding

November 29, 2017

No Comments

Seven collaborative and five solo albums into her career at 31, Esperanza Spalding has always resolutely, intuitively, deftly expanded upon both her art and herself

Tania León

November 29, 2017

No Comments

Highly regarded internationally as a composer and conductor, and recognized for her contributions as an educator and advisor to arts organizations, Tania León has established

Does all music need to be meaningful? What difference does it make?

November 12, 2017

No Comments

Music and societal happenings have always been intertwined. Music holds the power to reflect and create social conditions — including those that advance or impede