African-American Folk Music

Within African-American secular folk music, one will find a myriad of cultural textures and influences at work: the intrinsic ability to weave music into daily life that came by way of Africa, the toils and suffering through slavery, an affinity for rhythms and dance, as well as the flairs and particularities of the West Indies, French-Creole Louisiana, and other places. African-American folk music serves as some of the earliest music created by Africans and acculturated African-Americans in the midst of enslavement. The genre represents the many ways in which black folk created music in and of the moment – secular folk music speaks to the improvisation, ingenuity, and creativity also present in subsequent black musical styles. Work songs, protest songs, impromptu compositions for dances, and even children’s games centered in song, all came out of the black folk music tradition. The genre, in a way, represents the acculturation that occurred of black people brought to America – while the music teems with African musical references and influences, it cannot be denied that today it stands as an everlasting symbol of American life and tradition.

- Characteristics of the Genre -

African-American folk music can of course be distinguished by the instrument(s) being played or the way it sounds, but also through the specific circumstances through which the music was created. Many secular folk songs are categorized by the event or circumstance they were conceived in – as previously mentioned, work songs, game songs, and protest songs all constituted folk music. These folk songs often focus on the “now,” creating improved lines and melodies that tailored to the specific present moment at hand. For instance, work songs were created to sustain a rhythm for workers – such as the “gandy dancers,” or early railroad workers, pictured below – to follow through-out their strenuous work. Lyrics might describe the task at hand, or seemingly other common experiences to take one’s mind off of the grueling hours of hard work. Often times, leaders of a work group were indicated by how strong and easy to follow their voices were. Similarily, slaves working long hours in the fields or doing other labor often turned to song to fend off exhaustion, keep momentum, express their pain and suffering, and even allude to insurrection or escape through lyrics. In fact, within insurrections, dancing, singing, and making music had become such an integral part that drumming became banned across plantations.

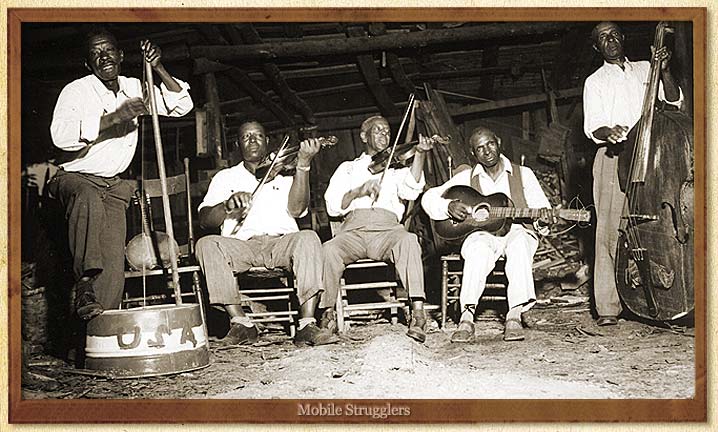

Dance in itself was a huge inspiration for folk music. Various types of dance – such as “la calinda,” a heavily French-Creole inspired dance, or the patting juba – often gave rise to music and various songs being created. This affinity to build song and dance off one another came from the enslaved African-American’s African roots, as dancing and celebrations were always an intrinsic part of life in African cultures. During slavery, dances that occurred during Sunday’s or special holidays brought black folk from all over, resulting in celebrations with dancing and singing that could last well into the early morning. It was at these celebrations, during which a fiddler, some drummers, and other musicians kept a lively rhythm, that many folk songs were made.

Musical elements such as call-and-response, improvisation, as well as the use of instruments such as the banjo, fiddle, and various drums also drove African-American folk music. Call-and-response is a prime example of folk music having come from early influences of African culture. In many African cultures, music was (and still is) always seen as a group activity, and call-and-response allowed for a group of singers and musicians to come together and respond to one another.

- Celebrated Folk Artists -

Because African-American folk music was so widespread and often created by various workers, slave hands, and common African-American folk, it cannot be pinned on particular artists as other musical styles might be. Still, even as a “music of the people,” there is a group of folk artists who are celebrated and revered for their contributions to the folk genre. Some are included below.

Lead Belly

Folk singer and guitarist, Huddie William Ledbetter – better known as “Lead Belly” – was born on January 20, 1888, in Mooringsport, Louisiana. He was known for his distinct style on the twelve-string guitar, however he played a myriad of instruments such as the piano, mandolin, harmonica, and accordion. He began playing instruments as a young child and participated in his school band until the age of 13. He soon left home, living in Shreveport, LA, and then Texas, supporting himself as a musician. It wasn’t until he was imprisoned for attempted murder in Texas in 1930, that he was discovered and made famous by two folk enthusiasts, John and Alan Lomax. After an early release, he made a career in New York City and later in Los Angeles following a second arrest. Lead Belly recorded and released some of his most well-known songs, such as “Goodnight, Irene” (featured on the left) and “Cotton Fields.” He passed away in 1949 after a battle with ALS.

Elizabeth Cotten

Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten was born on January 5, 1893, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the youngest of five children. At just the age of 7, she begin playing her brother’s banjo. At 11, after years of playing the banjo, Cotten purchased her first guitar. By her teenage years, Cotten was writing her own songs at home – “Freight Train,” one of her most popular, is just one of many. Still, Elizabeth Cotten did not perform publicly nor record her songs until she was in her 60s. Mike Seeger, a white folk musician from New York, NY, began making recordings of Cotten playing her songs in her home. Cotten’s created so much attraction amongst fellow folk musicians and folk revivalists – so much so that she began going on tours in various cities around America. In 1984, three years before her death, Cotten received the Grammy award for Best Ethnic or Traditional Recording for her album Elizabeth Cotten Live.

Odetta

Ms. Odetta Holmes, often mononymously known as “Odetta,” is a African-American folk artist and civil rights activist who was instrumental in the American folk music revival period of the ’50s and ’60s. Odetta was revered by musicians and public figures from all backgrounds – whether it was Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin, or civil rights greats such as Rosa Parks and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr (the latter dubbed her as the “Queen of American Folk Music”). Odetta, who was born in Birmingham, AL, but grew up in Los Angeles, CA, began singing professionally at 14 as an ensemble member with the Turnabout Puppet Theatre. However, she is most celebrated for her work as a solo artist. Odetta often sang traditional Negro spirituals and folk songs such as “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and “Santy Anno.” In 1963, she released an album entitled Odetta Sings Folk Songs, which remains as one of her most best selling albums today.

- Influences on Subsequent Musical Styles -

Secular folk music is often associated with Negro spirituals, as well as certain styles of blues and country music. Many facets of African-American folk music – lyrics rooted in freedom and anti-slavery sentiments, call-and-response song formats, and a long-cultivated aptitude for instruments such as the guitar and banjo – all show up in contemporary African-American styles of music.

- Social Impact -

The commodification of African-American folk music can be easily seen in the creation of the traveling minstrel shows that dominated both white and black entertainment in the early to mid-19th century. Minstrel shows – which are often known to depict African-Americans in “black face” and display the harmful stereotypes of black folk during the antebellum period – often took folk songs created by black communities and incorporated them into shows.

The TED talk on the right, entitled “Bones and Banjo: Confront Cultural Appropriation,” features folk musician Kafari who speaks on the appropriation of black musical styles and instruments from this genre.

- Personal Reflection -

Secular folk music continues on as a testament to the blooming creativity, to the inherent musical gifts, and to the collective soul of black folks. This music is essential, as it not only shows our early influences on music, but our historical ability to harness our struggle and suffering and reflect it in our art. I look to this early African-American folk music and artists such as Odetta and Lead Belly to understand our roots and our essence.